I’m in the process of tearing down the pedestal I’ve propped “perfect’ people on.

I’m finally recognizing how my vision — of a good life — of being a good person—- got thwarted, how it’s been narrowly defined, how those who I deemed led “charmed” lives – may also have unexamined lives, lives that lack multiple dimensions, lack creativity, lack versatility, and derive far fewer gifts the world has to offer, once they are accustomed to a routine of a life they[ve focused all their energy and being into building. They don’t have the courageousness those of us, who have seen our entire worlds fall apart, to build things from scratch, to rethink our choices, to try new things. That once they achieve a certain stature in their career, thet may never see how you might grow in different directions and can’t stomach the idea of being a novice and investing the energy to excel in anything new – even if something new doesn’t require excelling. Their lives have left them with no energy to spare.

The thing is that I may have propped perfect people on a pedestal, I may have kept them in my life, in a masochistic exercise, of a reminder of the fact that they have it all together and I’m a puddle of messiness. Depressed people love to hate themselves. But perfect people also propagate their own perfection. They are careful to maintain a veneer of perfectness, to rarely show vulnerability, to never truly express frustrations or complain (if they do so its with caveats that it’s all okay), to divulge anything that might destroy their own vision of themselves or the reputation they’ve earned from the world around them. They may still be humble, but they will not openly experience emotional strife, because then they come down to our levels. This cool control masks discontent, and reaffirms that they are far superior to us who are emotionally reactive and needy and unlucky, disabled, and flawed.

But vulnerability is what gives relationships, connections of every kind, depth. Reciprocal vulnerability is how you build meaning into these interactions. Shared activities, shared experiences also build bonds. But a Perfect Person has priorities, and while they might circle around to checking off the box of providing you emotional support for 2 hours every two months – it promotes the good person that they are — they do not need you, they do not need your company or want to lean on you. The shared experiences they choose to pursue with you can’t extend beyond their comfort zone, they don’t have the energy or imagination to envision anything beyond. They will do it upon your insistence, to placate you, to make you happy. But how is that a fulfilling relationship?

The irony is also that people are drawn to vulnerability, to messiness, to the realness. I’ve never recognized the asset of my own confessional nature, the intimacy I can build with little time. The way I put those around me at ease. Whether it’s those in an elite professional world, or fellow patients in the mental hospital, or people from entirely different nations, upbringings or classes than my own. I am not a saviour. I’m a real person.

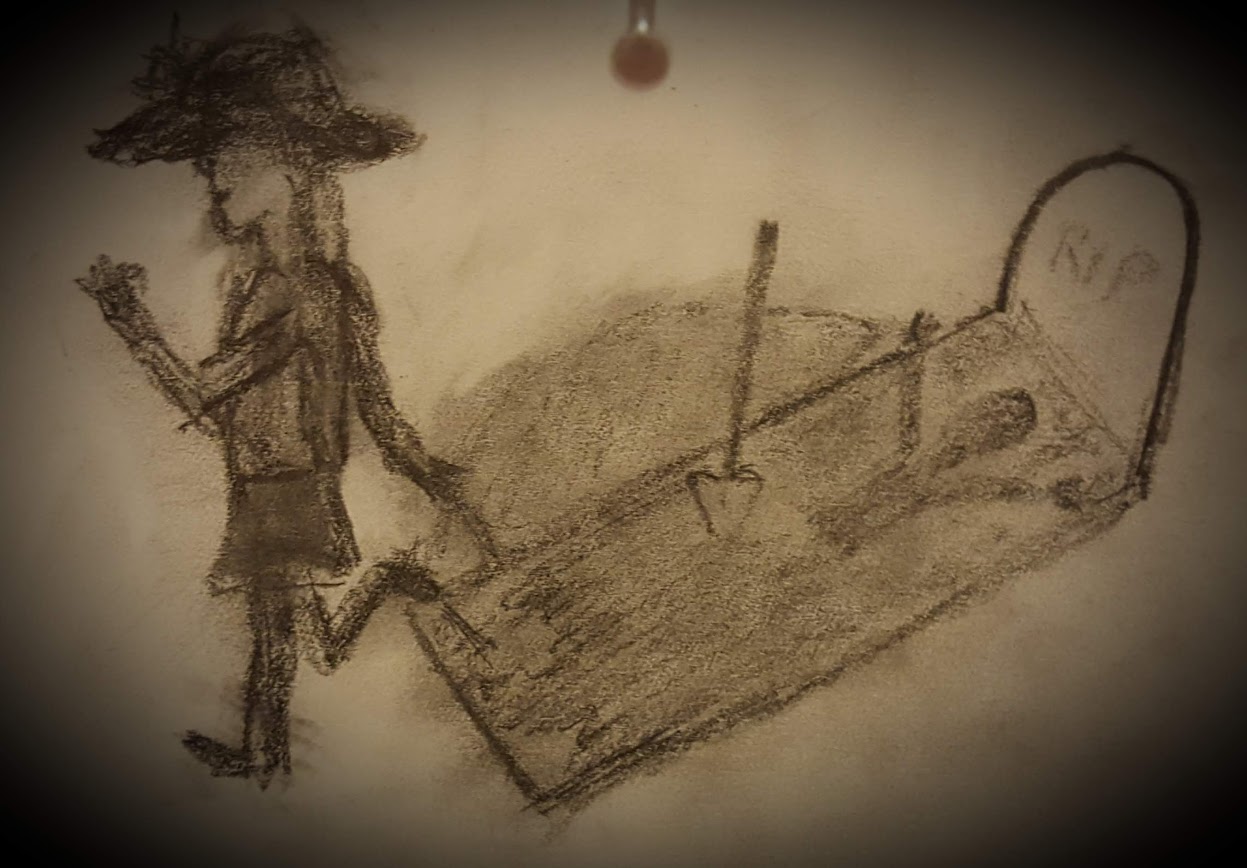

I am so far from perfect, when I reflect on the arc of my life, it just looks like a series of disasters.

From my fave School of Life on Overcoming the Need to Be Exceptional

“- It seems odd to look at achievement through this lens, not as the thing the newspapers tell us it is, but – very often – as a species of mental illness. Those who put up the skyscrapers, write the bestselling books, perform on stage, or make partner may, in fact, be the unwell ones. Whereas the characters who – without agony – can bear an ordinary life, the so-called contented ‘mediocrities’, may in fact be the emotional superstars, the aristocrats of the spirit, the captains of the heart. The world divides into the privileged who can be ordinary and the damned compelled to be remarkable.

…

Our societies – that are often unwell at a collective and not just an individual level – are predictably lacking in inspiring images of good enough ordinary lives. They tend to associate these with being a loser. We imagine that a quiet life is something that only a failed person without options would ever seek. We relentlessly identify goodness with being at the centre, in the metropolis, on the stage. We don’t like autumn mellowness or the peace that comes once we are past the meridian of our hopes. But there is, of course, no center, or rather the centre is oneself.

…

There is already a treasury to appreciate in our circumstances when we learn to see these without prejudice or self-hatred. As we may discover once we are beyond others’ expectations, life’s true luxuries might comprise nothing more or less than simplicity, quiet, friendship based on vulnerability, creativity without an audience, love without too much hope or despair, hot baths and dried fruits, walnuts and dark chocolate.

I love the idea of viewing achievement as the mental illness. Even those who strive and strive, to be more zen, the wellness gurus preaching their claims, seem to be in some kind of competition and that they are their own brand of perfect.

I’m messy, I am not zen, I am honest, I like to sit in the sunshine and stare at the clouds and admire the personalities of trees and I like to giggle with my nieces and nephews and — while I’ve been told and followed all of the things I thought I “should do” both to be successful in my career and to heal myself of my illnesses, I am finally navigating a place where I feel like I’ve found what truly gives me pleasure and completeness.

And I’m not putting myself on a pedestal, I’m not putting you on a pedestal. I’m tearing down the pedestal. I’m going to seek genuine moments with genuine people who derive something from me in our relationships and aren’t holdovers from the past who make me feel like they are my caretakers and I’m small insignificant person who offers nothing of equal value.